First Monday, October 2014, v19n10

“This video is not available in Germany”

Online discourses on the German collecting society GEMA and YouTube

Abstract

YouTube’s blocked content notice “This video is not available in Germany” is part of an ongoing discourse on music streaming and the German collecting society, GEMA. The debates unfold mainly online, and GEMA–bashing is one of the most recognized outcomes. The central question is: How much are music authors paid per stream? By conducting a critical online discourse analysis I identify central interests, arguments and discursive strategies in the discussions around GEMA and YouTube. I argue that positioning has become a central factor in these online discourses.

- Keywords

- discourse,

- analysis,

- online,

- YouTube,

- GEMA

Streaming is becoming a major means of music consumption today [1]: “Measured by the total volume of sales from music distribution in Germany, the share of streaming almost doubled from 2,5 percent in 2012 to 4,7 percent in 2013” [2]. Although streaming remains a supplementary revenue stream and physical music sales remain a stable and characteristic feature of the German music market, streaming is regarded as an increasingly important topic in the music industry. Until now, however, video platforms based on advertising have played a minor role in revenues, because of the ongoing struggle between GEMA and YouTube.

From the services’ perspectives, providers like YouTube and Spotify dominate the market. They shape music distribution at a rapid pace. Access to music as a service is their business model, not selling music files or records. The competition is fierce, however. For example, in spring 2014 new players like “Beats Music” and Amazon’s “Prime Music” entered the scene, while YouTube is planning a special streaming service focused on music. The same goes for video platforms.

It is no surprise that these fundamental changes are accompanied by heated discussions between all actors involved, from artists to distributors to consumers: musicians ask for better revenues out of streaming, music labels call streaming a “bridge to legality”, enterprises like Google try to pay as little as possible for copyright licenses, and consumers ask for cheap and convenient services. The German collecting society for authors and composers of music, GEMA (Gesellschaft für musikalische Aufführungs- und mechanische Vervielfältigungsrechte or Society for musical performing and mechanical reproduction rights), is situated in the middle of these discourses in Germany. Like other collecting societies, it tries to negotiate the best possible streaming licenses for members. But the long-lasting struggle with YouTube — at the moment at the arbitration board — became one of several disasters for GEMA’s public relations. YouTube blocks several videos in Germany while blaming GEMA. This is one of the reasons why the so-called “GEMA-bashing” became so popular in Germany, and thereby the collecting society faces strong criticism.

From an international perspective, the conflict between GEMA and YouTube is unique. Only in Germany is YouTube blocking videos because of its negotiations on licensing. But this singular national dispute indicates a more general conflict, and therefore it is of particular interest on an international level as well. The discourse exemplifies the structure of debates on the revenues of music streaming and digital music distribution, and those conflicts can be found elsewhere. By conducting a critical online discourse analysis, I will identify the central interests, arguments and discursive strategies in the respective discussions. Consequently, I address the following questions in this paper:

- What is the general technical and legal background of music streaming discourses? (Section 2)

- Which methodology is necessary to analyze the online discourses that surround the GEMA-YouTube conflict and which texts are relevant for it? (Section 3)

- How does positioning work in these discourses? More specifically: How are truths, symbols and “good”/“evil” tendencies used in respect to the positioning? (Section 4)

1. Technical and legal background of music streaming

A first thing to clarify very briefly is the legal and technical background of music streaming. From a technical perspective, streaming is a complex matter: “[...] a data stream is defined as an unbounded (or never-ending) sequence of data items [...]” (Chakravarthy and Jiang, 2009). Special streaming protocols send series of small data packets that enable simultaneously receiving and consuming of compressed videos and music. Because of bandwidth and processing limits, streaming music and videos had not been widely available before 2005. Up until that point, the twenty-first century’s discourses around “online music” were dominated by Napster, file-sharing, the legal discussions on music downloads, and the so-called crisis of the music industry (see A&M Records Inc. v. Napster, 2001). YouTube started its services in 2005, Spotify in 2008. While YouTube shows advertisements in order to finance their video service, Spotify is also offering paid subscription models. Overall, streaming is part of an ongoing process: away from possession by downloading files, and towards accessing online content hosted elsewhere (Dörr, 2012).

Due to copyrights, artists and composers have the right to get a share of the money that is earned if their work is exploited. In German copyright legislation “Urheberrecht” [3], the right of reproduction § 16 UrhG [4], and the right of making works available to the public § 19a UrhG [5], are key to streaming. They are the reason why contracts and licenses between collecting societies and services like YouTube have to be negotiated. In general, the authors (“Urheber”) have the right to receive fair compensation (right of equitable remuneration § 32 UrhG [6]), if others use their works. Besides those authors’ rights, related rights [7] for performers and recording producers have to be licensed as well (see Dam, 2013, for an exhaustive legal discussion of streaming).

2. Methodology: Critical online discourse analysis, theoretical sampling and MAXQDA

2.1. Critical online discourse analysis connected to positioning theory

For the analysis of discourses, a variety of socio-scientific methods are now available [8]. Many of them are derived from Michel Foucault’s theory of discourse, although he never developed a specific method. Foucault analyzes structured and structuring practices and power structures that are organized in systems of statements — the “atoms of the discourse” [9]. Besides discourse theory, the analysis of positioning in conflicts is the main theoretical subject of this paper. Following Tirado and Gaálvez (2007), I will use positioning theory in order to point out how the discourse participants position themselves and others, rather than assuming fixed and static roles (Harré, et al., 2009; Davies and Harré, 1990; Harré and van Langenhove, 1999; Allen and Wiles, 2013). Positioning theory distinguishes between position, speech act and storyline, resulting in the positioning triad that “can be usefully analyzed in terms of rights and duties” [10]. In order to bring discourse theory and position theory together, critical discourse analysis delivers a methodology that offers the possibility to examine social injustices, truths, collective symbols and rhetorics in discourses (Jäger, 2010, 2012). The goal of critical discourse analysis is the “identification of possible statements as atoms of the discourse” (Jäger, 2010, 2012). With reference to Keller, I analyze symbols and tendencies to distinguish between good and evil [11]. This leads to the following research question: How are truths, symbols and “good”/“evil” tendencies used in respect to the positioning?

More and more people use social media [12], and thereby the sociopolitical struggle for power and meaning on the Internet is gaining influence. Accordingly, online discourse analysis (Fraas, et al., 2013) becomes an important subfield of social sciences with its own set of attributes [13]. Controversial debates on copyright take place in online articles and commentaries. They are the material of choice for this paper. Prior to the text selection process, I would like to mention that I will not refer to particular posts with hyperlinks in order to protect the privacy of discourse participants that are partly private persons [14]. An inevitable problem comes also with translating the discourses from German to English. That is why I will avoid long direct quotations; shorter translated sections will be indicated using quotation marks.

2.2. Text selection via theoretical sampling and MAXQDA

Because it is almost impossible to collect the entire amount of statements and text of an online discourse, scholars suggest taking a “grab sample” [15]. That is why Meier and Pentzold [16] suggest Glaser and Strauss’ (2012) approach of “theoretical sampling” to structure the choice of texts in a systematic way. I came up with the following distribution:

| Type | Selected texts (number of texts) | |

|---|---|---|

| Newspaper articles | traditional | ZEIT Online (4), Spiegel (4), Welt (2), Bild (1), Tagesspiegel (1), Berliner Zeitung (1) |

| online focused | Heise (9), Golem (3), Musikmarkt (3), The European (2) | |

| Blog articles | iRights.info (3), Delamar (1), Neumusik (1) | |

| Interviews | YouTube/Latrache (1), GEMA/Heker (1) | |

| Press releases | GEMA (6) | |

| Comments | GEMAdialog’s Facebook page (3), jetzt.de (1) |

This discourse material is in a digital format, and coding this quantity of articles is a complex procedure. Therefore, the use of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software [17] is reasonable. Besides the frequency of occurrence of statements, the interlaced coding system of the software MAXQDA was of great use for the analysis and categorization of hundreds of different statements.

3. “This video is not available in Germany”: Discourses on GEMA and YouTube

3.1. Overview of the conflict

The discourse between the collecting society GEMA and Google’s YouTube attracted a great deal of media attention. GEMA “represents the copyrights of more than 67,000 members (composers, lyricists, and music publishers) in Germany, as well as those of over two million copyright holders all over the world. It is one of the largest societies of authors for works of music worldwide” [18]. As mentioned above, this is the reason why GEMA has to negotiate with YouTube, the biggest streaming video platform at present. According to YouTube, “more than one billion unique users visit YouTube each month”, “100 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute” [19]. Many contain copyright-protected music.

At the end of March 2009, the first contract between GEMA and YouTube expired. Since then, both parties are renegotiating a follow-up agreement, but they have not reached a settlement yet. In September 2010, GEMA and allied partners took YouTube to the regional court of Hamburg [20]. This led to a judgment, issued in April 2012. GEMA published a press release saying that according to the court’s decision, “YouTube is legally responsible for the contents of videos its users publish. This means YouTube has to initiate appropriate measures to make copyright protected works unavailable in the future.” [21] But according to the video platform, the court decided that their service is a hosting platform and not a content provider. Consequently, YouTube is not obligated to control all uploaded content [22]. YouTube states that it is liable only as a “Störer”, not a “Täter” [23]. After another pause in negotiations in January 2013, “GEMA has initiated proceedings at the arbitration board of the German Patent and Trademark Office. As a neutral body, the board will review whether the minimum compensation rate called for by GEMA is reasonable” [24].

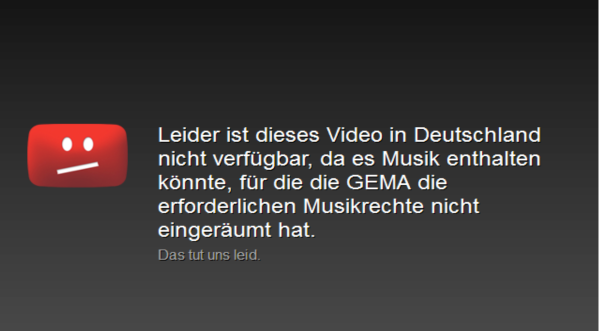

This conflict attracted wide public interest, mainly through YouTube’s blocked content notice that stopped users in Germany from watching videos with GEMA’s repertoire:

“Unfortunately, this video is not available in Germany, because it may contain music for which GEMA has not granted the respective music rights. Sorry about that.”

As reported by Musikmarkt, in early 2013, 60 percent of the most popular videos were blocked with the red grumpy smiley [25]. This is one of the most important reasons why the so-called GEMA-bashing emerged. GEMA is being held responsible for the blocks, resulting in “shitstorms” [26] not only on GEMA’s Facebook page “GEMAdialog”, demonstrations, and a hacker attack by Anonymous [27] that temporarily shut down GEMA’s Web site. GEMA was exposed to enormous criticism from the public and also from popular newspapers like Bild [28]. Regarding the wording of the blocked content notice, GEMA went to court once again. In February 2014 the regional court of Munich held that the phrase had to be changed because the statement was not true [29]. Since then, YouTube is showing a slightly adapted text:

“Unfortunately, this video is not available in Germany, because it may contain music for whose usage we have not reached an agreement with GEMA yet. Sorry about that.”

3.2. Structure of the analysis

The discourse analysis is structured according to the two phases of positioning:

“The act of positioning is a two-phase procedure. In the first phase the character and/or competence of the one who is being positioned or is positioning him- or herself is established. This can conveniently be distinguished as an act of prepositioning. On this basis, rights and duties are assigned, deleted or withdrawn, taken up, and so on.” [30]

Correspondingly, I will scrutinize GEMA’s and YouTube’s prepositioning first (Section 4.3 and 4.5). Then, I will analyze the online positioning against/towards the opponent regarding rights and duties that are expressed in the conflict (Section 4.4 and 4.6). Here, the positioning through online media also becomes relevant. Finally, I will situate the findings from this “public level” with respect to a “private/professional level” in commentary at GEMAdialog, and at one selected article (section 4.7). This follows Harré’s argument: “Private discourse should be viewed as being shaped by, and stemming from, public discourse.” [31]. Through doing so, we gain deeper insights into the mechanisms of public-private interactions in online discourses.

3.3. GEMA’s prepositioning

Generally, GEMA demands remuneration per stream. GEMA argues that their minimum request of €0.00375 should be considered a mandatory minimum, otherwise music would be used without an equitable compensation being paid. In 2013, GEMA announced two new rates for streaming services. These rates have been negotiated with the inter-trade organization BITKOM [32] and the collective of private radio and telecommunication companies VPRT [33] (including video platforms like Clipfish, My-Video.de, Tape.tv and Pupat). A quick glance at the details serves to illustrate the matter. The standard royalty for ad-funded and so-called “unlimited subscriptions” streaming services both amount to 10.25 percent of the computation basis. The royalty rates for the use of works from GEMA’s repertoire, within the scope of streaming offers subject to a fee (so-called “unlimited subscriptions”), are between six and nine cents (after tax) per music work (VR-OD 8 [34]). For ad-funded streaming services and high interactivity services, the minimum royalty is the aforementioned €0.00375 per stream (VR-OD 9 [35]). The obligation to pay royalties is based on the Urheberrecht described above. GEMA argues that the online consumption of music has resulted in a decline in record sales — the main source of income for a long period. But GEMA wants to ensure that the creation of works, which costs time, labor and money, is still possible. This shows how GEMA positions itself with respect to the legal framework. Urheberrecht is an apparently unquestionable point of reference, which delivers a “storyline”. The already established royalty rates support this argumentation: GEMA has reached agreements with players that accept the equitableness of the rates. By that, GEMA shows its own legitimacy, value and presence in the music market. Furthermore, GEMA is claiming to stand up for the artists in particular and music culture in general. The storyline mobilized by this position should annul any criticism from listeners, because it is not in their interest to make their favorite bands and artists disappear.

3.4. GEMA’s positioning regarding YouTube

The online texts analyzed showed that GEMA blames YouTube for conducting discussion in a “destructive way”. According to GEMA, YouTube has stopped the negotiations repeatedly, and rejects all proposals of fair remuneration. As mentioned above, the main interest for GEMA was in determining that YouTube is liable via the Störerhaftung. For GEMA, the ruling in Hamburg showed that YouTube bears responsibility. The platform is obliged to use music identification and word detection software in order to control uploads by users. For GEMA, YouTube clearly is a content provider, and not merely a hosting platform. The collecting society claims that YouTube uses the videos commercially by monetizing them with advertising and thus appropriating the content that is shown. With this business model, Google earns billions of dollars a year, but in line with GEMA, YouTube does not take the intended “normal” legal action, namely: to ask the arbitration board as a neutral party to decide about the fairness of streaming royalties, and to deposit the contested amount with them at the same time. Since YouTube does not take these steps, GEMA feels compelled to sue YouTube for €1.6 million in damages, and let the arbitration board decide whether GEMA’s minimum request of €0.00375 per stream is equitable. GEMA thus positions itself as the party standing for the “normal” and “fair” solution. YouTube allegedly does not recognize its responsibility, and therefore is being positioned by GEMA as breaking up negotiations over and over again. This is why GEMA claims to have the right and the duty to sue YouTube and to clarify fair royalty rates.

GEMA underlines this positioning with respect to YouTube’s blocked content notice. The collecting society states that the blocking is an “absurd game”, because the video enterprise blocks the videos on its own; no one else has the ability to block the videos. Nevertheless, YouTube presents GEMA as being responsible. Therefore, GEMA’s representatives state that the public is influenced in a “very misleading way” by the notice, and that this is an “illegal slander and a vilification”. Reflections from GEMA’s side say that the clever marketing action passes the buck to GEMA, and therefore the collecting society has become the “evil” party and a kind of “national scapegoat”. Expressions of contempt are made on a daily basis, as GEMA is perceived to prohibit the consumption of music. In reaction to the court decision on the notice text, GEMA tried to emphasize that YouTube was “defeated”. GEMA even produced a video [36] in which the conflict between GEMA and YouTube is outlined in order to influence the public discourse. It accentuates the word “rechtswidrig”, which means that YouTube’s wording was unlawful. The following statement by GEMA, which showed up in many texts, is also striking: “YouTube is creating a wrong impression.” By these means GEMA positions itself as not being responsible for the blocked videos. Instead, GEMA tries to make the public aware of YouTube’s “misleading” marketing. GEMA thereby tries to position YouTube as a company that deserves little or no respect because of its deceptive publicity. Keller’s “good vs. evil” contrast is thus deployed [37], with the objective to position GEMA as good, and YouTube as evil. However, this also illustrates how the blocked content notices force GEMA into a defensive position. This positioning is linked to the so-called “GEMA-bashing” (section 4.7) and to the public pressure initiated to some extent by YouTube’s blocking. Trying to question YouTube’s famous accusation, GEMA’s statements display this tension and references to rights (“unlawful”) very obviously.

GEMA also questions YouTube for not providing information on its scope of profits, losses and volumes of sales. Because of this lack of transparency, defining the equitable remuneration demanded by law is a difficult endeavor for GEMA. Moreover, the nondisclosure agreements that Google signs with business partners could not be accepted by GEMA, because the society is obligated to report on negotiated rates. It becomes apparent that the collecting society shapes the picture of YouTube as a nontransparent business player, earning a great deal of income with its services while hiding financial details. GEMA focuses on YouTube’s secrecy, which it highlights as an unfair practice. According to GEMA, YouTube should be forced to disclose its financial details.

Overall, GEMA sees itself in a defensive position, because of the criticism indicated above. These statements clearly show GEMA’s struggle to productively shape the discourse to the organizations advantage. We will consider the impact of the discourse by analyzing debates on Facebook and in comments in section 4.7.

3.5. YouTube’s prepositioning

In contrast to GEMA’s position, YouTube does not regard itself as a content provider, and sees itself supported by the court in Hamburg which, according to YouTube, stated that its legal status is as a hosting service: “As a hosting platform we have no influence on what users are uploading” and “pre-checks cannot be realized practically.” Moreover, for hosting services, leaving the contested monies as security at the arbitration board (as GEMA asked) is neither practicable nor entailed in any way. This general classification as a hosting platform entails a legal and economic position that frees YouTube from several restrictions and duties that content providers are subject to. As we already have seen, GEMA claims exactly the opposite. During recent years, this provider/host opposition has blurred, making a precise distinction more difficult. Hence, the legal consequences of this determination are important and a central and controversial matter in the discussion. In asserting that the service has “no influence” on uploads, YouTube delivers a storyline of a free and uncontrolled Internet. Nevertheless, it is doubtful (and GEMA has doubts) that YouTube would not be able to conduct pre-checks, given its Content-ID [38] and personalized commercials appear technically feasible and functional. But YouTube positions itself in this way and thereby also distinguishes itself from GEMA on the basis of rights and duties. For YouTube, the prepositioning as a hosting platform serves as the central argument why the step to deposit with the arbitration board has not been taken.

YouTube often states that it takes the protection of copyrights seriously, and removes videos once right-holders claim a violation of their rights. Via Content-ID, those right-holders also have the possibility to identify works, to block or monetize them while having insight into statistics. Examples like Psy’s “Gangnam Style” [39] or Baauer’s “Harlem Shake” [40] have shown how powerful and successful incomes through advertising can occur if creators decide to participate in the parodies fans make and post online. This is a strong prepositioning as a copyright-respecting and monetizing service. The aim of these statements is clearly to show how artists and right-holders can profit from YouTube’s possibilities and offers while enforcing their rights. For YouTube, some successful examples serve as a point of reference to what monetization can or should look like in a digital music industry. This is part of a general storyline that describes a rather bright, optimistic and positive online future of music, instead of a grim or disheartening one. Working together with YouTube is thus positioned as the right path to take.

3.6. YouTube’s positioning regarding GEMA

In reaction to GEMA’s call of the arbitration court, YouTube presents itself as being “surprised and disappointed” about GEMA’s legal action: “This is naturally complicating negotiations.” In every public statement and in almost every article, YouTube clarifies its cooperation with GEMA: “At any time we are open for new conversations with GEMA. GEMA is the one who does not continue the negotiations.” In addition, YouTube states that it is willing to share in its advertising income. But the crux for YouTube is GEMA’s minimum request. The video platform does not have a fixed turnover per stream, and that is why GEMA’s minimum request of €0.00375 is not acceptable; nor does it match YouTube’s business model. The first thing to notice here is that YouTube takes the role of being the one who is open to conversation and seeking a solution. This puts GEMA in a negative position, while YouTube does not see a reason for GEMA’s refusal. This is underlined by YouTube’s offer to share income with GEMA and with artists, leading to an image of YouTube as service that is forced into blocking videos, although it is absolutely willing to pay and to find a solution. By putting GEMA’s ‘per-stream and minimum request’ at the center of the dispute, YouTube again blames GEMA and loads duties onto GEMA. Moreover, YouTube’s business model is positioned as being fixed: the royalty rates have to adapt. Following these positions, YouTube is presented on an emotional level as “surprised and disappointed”, while GEMA is obstinate and irascible. This is a personalization, aiming for more sympathy for YouTube’s position. All of this is based on YouTube’s positioning being on the “right side” of the dispute.

Another point of interest is how YouTube describes the future optimistically: “We are confident that we will find a solution in Germany, too.” According to YouTube, this will open up new income sources for musicians, as it is already working with “24 other collecting societies in 42 countries” where accounting does not function per stream. Similar to Spotify and other streaming services, YouTube presents itself as the new path out of the music industry’s crisis towards new business models that are part of a paradigm shift. This optimism, in conjunction with this international perspective, is an important part of YouTube’s positioning. The video platform seems to see itself as a new income source, which does not stand in contrast to established income flows via collecting societies. The comparison with other countries is often restated in commentaries, as we will see in section 4.7. It draws its energy both from showing that YouTube’s argumentation is accepted elsewhere, and from presenting GEMA as an exceptional case. Already in the blocked content notice itself the uncommon case of Germany (“in your country”) is a principal standpoint.

With regards to YouTube’s blocking practice, YouTube’s German press officer declared: “The wording [of the blocked content notice] is absolutely correct.” After GEMA’s success at the regional court in Munich in early 2014, YouTube nevertheless changed the text slightly, as we have seen above. Now it says that a settlement with GEMA has not yet been achieved. According to YouTube, until an agreement has been found the blocking will remain necessary. The rationale for continuing to block videos is that YouTube has no insight into lists of the actual GEMA repertoire, resulting in high and unpredictable financial risks for YouTube. This is “unfortunate”, as indicated in the notices, and YouTube tells consumers that the service is sorry for that. Besides criticizing GEMA, the text therefore is also an excuse. Once more, this shows how YouTube positions itself in the discourse in a remarkable way. By pointing out two main reasons (the minimum request per stream is too high, and there is no insight available into the GEMA repertoire list) that depend on its opponent’s actions, YouTube presents itself as having no possible solution other than to continue the blocking. Accompanied with the apology for the blocking, YouTube manages to keep up the goodwill of the users. They tend to point their anger and irritation rather towards GEMA.

3.7. Discourses in social media: GEMA-bashing or dialog?

The conflict and this (pre-)positioning is mirrored in the discussions that take place in social media. As we will see, almost all of the opponents’ positions are retaken in discussions among private individuals and media industry professionals.

GEMA has established “GEMAdialog”, both on Facebook [41] and on Twitter [42], where announcements are made and questions are answered for the purpose of enabling dialogue between interested persons, GEMA members, and GEMA’s staff. The Facebook page, with 11,340 likes as of August 2014, is particularly a site for controversy and debates that shed light on the reception and attitudes of consumers. Another important source for these insights is the comments found under articles. I chose to analyze the comments of jetzt.de’s article “Die Dummheit der GEMA-Hasser” (“The stupidity of GEMA-haters”), which triggered quite some reaction due to its polemic tone.

Before we get into the analysis of these social media discourses, it is important to take two aspects into account. Firstly, online statements and rhetoric should not be compared with other forms of statements, because some of the key features of computer-mediated communication [43] to be found in comments are non-synchronicity, persistence and anonymity. Secondly, Facebook names and nicknames suggest that male users dominate in the comments. They cannot therefore be regarded as being representative of consumers.

General GEMA criticism

In recent years, several narratives and storylines of GEMA criticism have evolved, and it is no surprise that they play a vital part in the discourses on music streaming. A fundamental point of critique involves GEMA being described as functioning like a “civil service” that performs “oversized administration operations”. The “chief of GEMA” is especially blamed for earning too much money. Furthermore, resistance to GEMA’s internal distribution system is expressed frequently in comments referring, for example, to “Dieter Bohlen & Co.”. In other words, a few GEMA stars are accused of earning too great a proportion of the distributed royalties. According to critics, only these five percent are allowed to vote in GEMA’s system. Due to this “undemocratic system”, 65 percent of the royalties are paid to only five percent of the members. In addition, music publishers are also members of the collecting society [44]. Critics therefore describe GEMA’s continually referring to artists as a “propaganda trick”. Based on the “fact” that the faults in the distribution system, non-transparency, complexity, and the incorrect measurement of work performances present insurmountable problems, some commentators threaten GEMA that it will never recover its legitimacy and the support from the people that are asking for fair compensation of authors.

Another aspect is the so-called “GEMA assumption” [45], that authorizes GEMA, as the biggest music collecting society in Germany, to generally assume the exercise of the rights of their beneficiaries. This is why event hosts and organizers are obliged to prove that no content derived from GEMA was used in GEMA-free events. But if only one song is from the GEMA repertoire, the whole concert or party has to be licensed with GEMA. Critics claim that the fee charged in those cases will never reach the authors that would deserve it. Through terminology such as “monopoly position”, GEMA is positioned as a powerful and repressive “public authority”. Some commentators also hope that the almost established GEMA alternative, C3S (Cultural Commons Collecting Society [46]) could repeal or undermine GEMA’s authority. Closely connected to this is another discourse developing around new GEMA rates for clubs [47].

The general GEMA criticism is in some cases accompanied by fundamental skepticism about intellectual property. This discursive position is found in several contexts around copyright and Urheberrecht. An argument is advanced that the comparison between digital and real goods, as undertaken in the article “Die Dummheit der GEMA-Hasser”, is flawed because the reproduction of an immaterial good is supposed to not constitute theft — a position also presented by the Pirate Party, for example [48].

These points of general GEMA criticism are among the most frequently found in the analyzed sections. In general, they can be regarded as forms of resistance against power structures [49]; they build storylines and a background for the expression of GEMA criticism in the context of the YouTube dispute.

GEMA criticism and bashing in the context of the YouTube dispute

By far the most frequently raised point of critique in the context of the struggle between GEMA and YouTube is the following: “Everywhere it works except in Germany — that can only be GEMA’s fault.” As with YouTube’s argument, commentators also refer to foreign collecting societies that have found solutions regarding the licensing of the video platform. Sometimes even the narrative of a “unique German path” is used, invoking Germany’s unique Nazi history. Over and over, GEMA is accused of having blocked a certain video on YouTube and of “preventing cultural artifacts from being shared and spread”. These assaults on GEMA’s legitimacy are often accompanied by negative narratives and collective symbols linking GEMA’s actions to historical memories, such as: “GEMA is censoring.” As already discussed in section 4.6, this gives a striking example of how commentators retake and internalize the “exception position” also presented by YouTube. Furthermore, the position is even refined further by linking it to history and through exaggeration. This delivers a strong backbone for countless accusations at GEMAdialog of GEMA’s blocking: “Others can see the video, only we cannot.” For most of the users who blame GEMA, it seems to be indisputable that GEMA and not YouTube block videos. They position themselves as having the right to watch videos, and so GEMA has to stop its practice. The effects of YouTube’s blocked content notice and YouTube’s prepositioning on users thereby become visible. Without going more into detail here, this shows again how companies like YouTube are able to influence individuals. The manipulation of public opinion becomes even more obvious when YouTube’s statements like “It is not the case that we do want everything for free” or “artists can get a share of ad revenues if they become YouTube partners” are duplicated in comments from users. The reasons for these repetitions cannot be carved out in this analysis. However, YouTube’s presentation seems to be very convincing, well presented or well-matching to users’ opinions.

In reference to a storyline of general GEMA criticism, the phrase “GEMA propaganda at its best” takes the same path. Critics present themselves as unable to comprehend GEMA’s repeated denying of its wrongdoing in relationship to the blocking notices. For those critical commentators, the original blocked notice text did not contain a false statement, because the collecting society obviously prevents a settlement. Here, commentators are repeating YouTube’s position on the correct wording again. According to them, the costs of losing YouTube’s income stream are borne by artists, users, labels and Google. This leads to the opinion that GEMA is actually harming artists with its “excessive demands”, rather than supporting them. Reversing the picture of GEMA as a supporter of artists (as described in section 4.3), GEMA is instead presented as being involved in a damaging and “excessive” activity. For example, in order to support this argument, one commentator presented calculations that suggest that one-tenth of GEMA’s position, thus €0.000375, would be acceptable as a payment per stream. Only a few commentators acknowledge and deal with GEMA’s actual requests in this way.

In the YouTube-GEMA discourse, the points of critique mentioned above are supported by rhetoric that go hand in hand with general criticism of GEMA. GEMA

- is ridiculous: “The biggest kindergarten in the nation”; “A ridiculous agglomeration of bureaucratic posers”

- should be abolished: “GEMA is illegal”; “Abolish with a referendum!”; “When is GEMA going to be dissolved?”; “GEMA nach Hause!” (wordplay that can be translated as “GEMA go home!”); “No one needs GEMA”; “For me, GEMA is the biggest pig in our country”; “GEMA has skeletons in the closet”

- is harmful: “The industry is enslaved by GEMA”; “GEMA is denying cultural diversity”

- is not up to date: “GEMA is a dinosaur”

- is “greedy” and “cutthroat”

- is rich: “GEMA has more than enough money”; “The association is throwing money down the drain”

These kinds of statements are clearly intended to bash opposing discourse participants and their positions. They exaggerate, they often deny ‘facts’, but most importantly, they make use of well-known negative or ridiculous cultural symbols and storylines. The term “GEMA bashing” points to this form of polemic positioning, which can be regarded as a form of subversive empowerment against the Urheberrecht hegemony represented by GEMA (section 4.3). The bashing engages with the positioning of GEMA in a very productive way in the analyzed comments. But if we look beyond Facebook and comments on articles, GEMA bashing can also be found in news platforms like techdirt (“Poor sweet, sensitive GEMA” [50]) or Bild.de, the Web site of the newspaper with the highest circulation in Germany. The latter published an article on the conflict in the Ukraine using “GEMA is blocking the cameras on Maidan” [51] as the title.

Defending GEMA

On GEMAdialog’s Facebook page and in the jetzt.de comments, several participants defend GEMA against the aforementioned criticism and bashing. The most common response on GEMAdialog to accusations of blocking is: “GEMA is not blocking videos.” Therefore, defenders stress GEMA’s legal obligation to contract with everybody: “GEMA is required to license music services”. Again, this shows a repetition of official arguments in the discourses in social media and comments. In the analyzed texts, it is striking that clarifying and telling the “true story” of the conflict become important goals. Supporters emphasize that GEMA is not technically able to influence YouTube’s video system. This displays the combination of two discursive strategies: Firstly, the defense of GEMA clarifies who blocks the videos. Secondly, this is connected to legal and technical ‘facts’: GEMA has neither the right nor the technical capacity to block videos. In this argument, information and facts are used with the intention of repositioning GEMA in response to the blocking accusations. This shows how the mobilization of facts in the “regime of truth” is tied to power relationships [52].

GEMA supporters also point out the “precarious income” situation of many musicians. Only a few can live well solely on the earnings from their music. Defenders underline that GEMA’s aim is to improve all revenue streams for its members. GEMA supporters are additionally trying to deconstruct GEMA’s public image by stating that the collecting society is not a “dead association”, rather: “musicians are GEMA”. They emphasize that everybody who says “fuck GEMA” implies “fuck musicians”. This is what GEMA’s press coordinator Goebel announced in 2013. In order to improve GEMA’s image, musicians should take an active part in the process of opinion formation. Those reactions show how GEMA’s defenders are repositioning the collecting society. They also counter criticism with personalization, by carving out the involvement of musicians and raising awareness of their difficult financial circumstances. Directly replying to criticism, deconstructing arguments and offering alternative readings are discursive methods that can also be identified here.

Overall, the defenders see no alternative to collecting societies, because negotiating with every licensee is not practicable for an author on his or her own. This general support for collecting societies that negotiate with industry players is a point of reference often implemented by GEMA defenders as proof of their indispensability. Moreover, they support GEMA in the confrontation with YouTube and Google, arguing that the contracts that have been signed between YouTube and other collecting societies abroad are completely “unacceptable”. These collecting societies have been outmaneuvered into giving away their rights for “ridiculous minimum stakes”: “GEMA has the balls to resist YouTube’s dirty campaign and to stay firm against offers of way too little.” The German situation is compared to that in other countries where solutions with collecting societies have been found. The contracts negotiated elsewhere are criticized. GEMA thereby is often described as the “last resistance” towards big players like YouTube, who would dictate the licensing conditions should “GEMA’s refusal” fail. This move also passes criticism on to the foreign collecting societies for not bargaining strongly enough. A solution in GEMA’s favor in Germany is therefore positioned as a possible starting point for international improvements in the income situation for artists.

Likewise, another strategy can be seen in the ongoing attempt to direct readers’ attention to the billions of dollars YouTube earns with its service based on creative works. Google’s monopoly position is described as the “real threat” in this struggle. GEMA defenders explain that YouTube does not see itself as responsible for licensing the service, as it insists on being only a hosting platform. In other words, the supporters position Google as a company that does not want to pay artists at all. Additionally, and in reference to a famous radio interview with the German singer Sven Regener [53], those participants criticize the everything-for-free mentality (“Umsonstmentalität”) around YouTube and Google’s refusal to find a solution with GEMA. Accordingly, they underline that creative works do have a (monetary) value [54]. This is a strong positioning of YouTube as a monopolist that does not want to pay artists. It directly contradicts YouTube’s claims (see section 4.5). The storyline of an everything-for-free approach is linked to YouTube’s presumed underlying intentions and its massive profits. It is a resistance against the devaluing of artist’s work [55].

Lastly, the defenders praise GEMA for its work. Participants declare in the comments that, although there are always issues, GEMA is actually working very effectively. The adjustment of the distribution system is described as an ongoing process, which is very complex due to the nature of the music business. Administration costs are only between 14 and 16 percent, and GEMA is not allowed to make any profit. This challenges the arguments mentioned by the critics of GEMA about the society’s inefficiency and high administration costs. Moreover, supporters of GEMA admit the difficulty of a fair distribution system; such a system would always be open to criticism. This positions GEMA as a society that works on betterment for artists and music fans with very low administrative costs. Moreover, this raises the indirect question regarding the alternative collecting society C3S: Who could do it better than GEMA?

Defending GEMA against bashing

According to GEMA defenders, the bashing comments reveal the “success of YouTube’s brainwashing”: “Millions repeat what YouTube is claiming against GEMA.” They argue that most of the statements by GEMA bashers are examples of prejudice and ignorance, while also being disrespectful and arrogant. “Study the German Urheberrecht!” is a request that is often used by pro-GEMA participants. Alongside these strategies, the defenders try to get rid of a general myth: They claim that income from YouTube’s advertising system cannot make up for the low royalties. For them, YouTube is instead increasingly “cannibalizing” physical sales and streaming subscriptions. The “cannibalizing” terminology shows again how YouTube is described as a threat. Defenders position themselves as the “knowing ones” while declaring that the critics do not have a clue about Urheberrecht and the music business. By doing so, critical participants are marked as “unknowing ones”, who have no right to criticize in the way they have done. Here, “The struggle about the truth” and “discursive dominance”, as Nonhoff describes, become clearly visible [56].

In a similar way, the defense responds to the bashing of GEMA’s internal structure and its distribution system: “Leave that to us — the pros, lawyers, industry and the judges”; “Criticizing GEMA is okay, but the resentment against their members is a serious problem.” For example, defenders mention that associated members also have rights to control and change GEMA, and the payout of the royalties is as fair as possible: “If you do not have success as an author, GEMA should not be blamed. If you sell an equivalent amount, you get the same royalties out of that.” Parallel to the aspects mentioned above, GEMA supporters refer both to the justice of the internal distribution system, and the democracy of its voting system. Following on from this point, the bashers can be partly positioned as unsuccessful frustrated authors. And again, the subject should be left to “us”, the professionals. This builds a community that strictly distinguishes between “us” and “them”, professionals/insiders and amateurs/outsiders. The latter are thereby positioned as not having the right to judge the internal system and the complex nature of GEMA’s structure and role. But even some GEMA supporting participants are also giving up. They think the “educational approach is pointless” if GEMA’s degree of popularity remains as low as it has been and GEMA bashers continue to refuse to listen to other opinions.

The complexity of the ongoing debate concerning GEMA and YouTube has been demonstrated by means of a critical analysis of the different players’ statements and their representation in digital media. Positioning theory has been used as a theoretical framework to structure the analysis, highlighting how prepositioning and positioning are important features in the discourse. The analysis of the discourse around GEMA and YouTube shows how struggles about positioning, truths, and opinion leadership take place online. I collected the main positional findings in the following table:

| GEMA | GEMA defense | GEMA criticism and bashing | YouTube |

|---|---|---|---|

| prepositions itself mainly through claiming rights (Urheberrechte) | prepositions the positive effects of its service for musicians and the possibilities of monetizing videos | ||

| positions YouTube as a content provider | prepositions itself as a hosting platform | ||

| accentuates that GEMA is not responsible for YouTube’s blocking practice | accentuates that GEMA is not responsible for YouTube’s blocking practice | accentuates that GEMA is responsible for the blocking | accentuates that GEMA is responsible for the blocking |

| positions YouTube as the one who refuses negotiations | positions GEMA as refusing negotiations, while claiming its own willingness to negotiate and its optimism towards a solution; personalizes itself as being surprised by GEMA’s legal actions | ||

| claims a “normal way of reaching a solution”, while stating that YouTube breaks up the negotiations | claims that GEMA is breaking up negotiations, while stating that the “normal way” is not applicable for the case | ||

| positions the settlements between foreign collecting societies and YouTube as unacceptable | positions the settlements between foreign collecting societies and YouTube as unacceptable | compares the German situation to foreign countries where settlements have been achieved | compares the German situation to foreign countries where settlements have been achieved |

| refers to already established rates in order to show their fairness and their capability to function in the digital music industry | states that GEMA’s rate does not fit YouTube business model | ||

| positions YouTube as a nontransparent business player and a monopolist | positions YouTube as a nontransparent business player and a monopolist | ||

| uses personalization in reference to artists in order to support GEMA’s position | uses personalization in reference to artists in order to support GEMA’s position | accentuates revenue for artists and labels via YouTube’s Content-ID | |

| requests a minimum revenue per stream | focuses on two points of criticism: (1) minimum request is not acceptable and (2) YouTube has no insight into the list of GEMA repertoire | ||

| positions itself as protecting copyrights and claims that YouTube wants everything for free | positions itself as protecting copyrights seriously | ||

| points out GEMA’s efficiency and optimization of revenue distribution | criticizes GEMA’s inefficiency in revenue distribution | ||

| positions critics as “unknowing ones” and defines a border between professionals and amateurs | positions GEMA supporters as out-of-date (more examples of GEMA bashing in section 4.7) | ||

| deconstructs YouTube’s opinion leadership and falsifies its arguments | uses extreme forms of collective symbolism and storylines |

As a conclusion, participants in the online discourse on GEMA and YouTube applied strategies like personalization, deconstruction, comparison, accusations of non-transparency, references to rights or business models, claims of injustices, and claims to possession of the “true story” or “the facts”. The use of rhetoric, collective symbols and storylines shows clearly that an existential fight is occurring, where opponents come to polarize each other and show resistance against power systems. Most actors utilize “good vs. evil” to position themselves and their opponents. Moreover, the analysis shows how private and professional participants reproduce positions from their supported institutions and exaggerate or refine them. YouTube’s blocked content notice became a huge success for the platform in terms of opinion leadership and providing ground for the bashing of its discursive opponent GEMA. Similarly, the analysis of articles and discussions in social media indicated that GEMA and its supporters try to reshape the discourse in their favor.

This analysis can only be a first step to analyzing the whole discourse in greater detail. Future research should focus on the discourses on a micro-level, scrutinize the role of digital media, and check for similarities or differences with other related discourses. Furthermore, artists’ involvement in the discourse should be analyzed. As an outlook, the GEMA-YouTube discourse is part of a whole system of interwoven discourses on how digital media is changing traditional business models and the work of artists. For example, a similar discourse takes place regarding Spotify’s royalties, where artists like Thom Yorke and some independent labels assert that the service pays too little. The same is occurring with traditional newspaper and book publishers versus online industry players such as Google and Amazon. These debates will not lose relevance any time soon; their topics are fairness and money in a period of a fundamental change for the music and media industries.